The world’s largest public funder of biomedical research is in limbo.

The National Institutes of Health has, in large part, managed to withstand the Trump administration’s attempts to slash its budget and upend how it distributes grants, thanks to decisions from the courts and Congress. But the agency now faces a growing vacuum in leadership in its top ranks — one that offers the administration a highly unusual opportunity to reshape NIH to its vision.

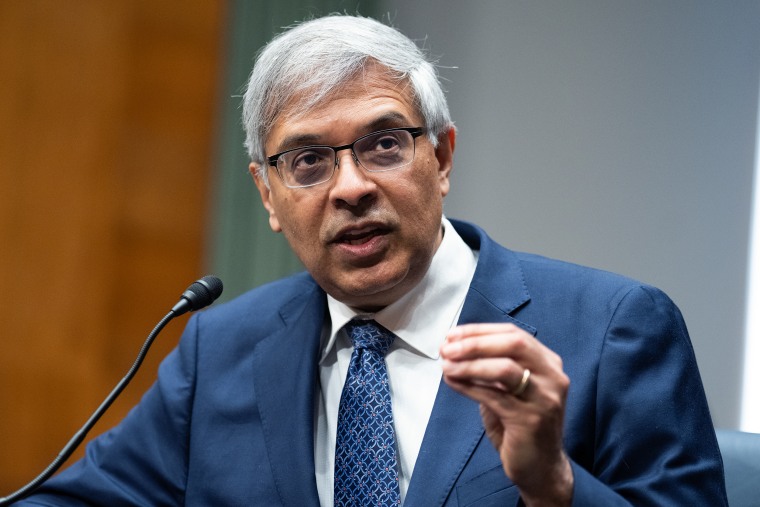

Of the 27 institutes and centers that make up NIH, 16 were missing permanent directors as of Friday, when staff received news of the latest departure. In an internal email viewed by NBC News, NIH Director Jay Bhattacharya announced that Dr. Lindsey Criswell would no longer direct the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases, effective immediately.

All but two of the vacant director positions at NIH have opened during President Donald Trump’s second term — the result of a combination of terminations, resignations and retirements. Acting directors are filling in temporarily.

“It’s like going to battle with half your generals in place,” said Dr. Elias Zerhouni, who led NIH from 2002 to 2008 under President George W. Bush. “I don’t think it’s precedented to have so many vacancies so fast.”

NIH director positions are some of the most powerful and prestigious in medicine, in some cases overseeing multibillion-dollar budgets and helping to decide how federal research funding is allocated for the country’s biggest health threats, including Alzheimer’s, diabetes and heart disease. They are typically nominated by the NIH director then approved by the health secretary. One of the most prominent figures to hold such a role in recent years was Dr. Anthony Fauci, who led NIH’s National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases from 1984 to 2022.

The vacant roles are especially significant given that some of the administration’s biggest attempted changes to NIH haven’t come to fruition. Judges ruled against a cap that it tried to impose on government funding for the overhead costs of research, and Congress last month awarded NIH a modest funding increase for 2026, rebuffing Trump’s request to slash the agency’s budget by 40% and consolidate its 27 institutes and centers into eight.

For much of its 139-year history, NIH has been a quiet, nonpartisan nest for scientific breakthroughs, helping fund research that has led to the development of HIV treatments, Covid vaccines and cancer drugs. But several current and former staffers told NBC News that they worry the agency will become more politicized depending on whom Health Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr. approves to fill the open director positions.

“I’m not confident that their appointments will be with the institute’s mission in mind,” said Shiv Prasad, a scientific review officer at NIH. “I think you’re just there to be compliant with whatever the HHS secretary wants done.”

Andrew Nixon, a spokesperson for the Department of Health and Human Services, said in a statement that “NIH is committed to filling all Director positions and advisory panels with the most highly qualified and meritorious individuals, ensuring expert representation to address the chronic disease epidemic and uphold gold-standard science.”

“This Administration is strengthening scientific rigor, restoring accountability, and refocusing NIH on evidence-based research that serves the health needs of the American people,” he added.

Bhattacharya did not respond to an NBC News inquiry about when he plans to fill the vacant spots or with whom.

‘Speaking up and pushing back’

Turmoil and turnover in the top ranks of the country’s public health agencies have become somewhat common under Kennedy’s leadership, with perhaps the most visible examples at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Kennedy fired CDC Director Susan Monarez, whom Trump had nominated for the role, just 29 days into the job. She later said it was because she had refused to blindly approve vaccine guidance changes. Several other CDC officials resigned in protest. After that, the agency reduced the number of vaccines recommended for all children and rewrote a webpage to reverse its long-held position that there’s no link between vaccines and autism.

Several NIH staffers said they have witnessed a similar situation.

“What was happening at NIH was entirely consistent with the mindset that was being promulgated much more publicly and sort of visibly at the CDC,” said Dr. Jeanne Marrazzo, who succeeded Fauci as the director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) from 2023 to 2025. “A lot of what has happened at NIH has not really been in the public eye.”

When Marrazzo inherited the position, NIAID was already under scrutiny from Kennedy and some Senate Republicans who opposed Fauci’s response to the Covid pandemic. Marrazzo was placed on administrative leave in April, then Kennedy fired her. NIAID remains without a permanent director.

Marrazzo believes she was removed partly because of her defense of vaccines, and for speaking out against the cancellation of NIH research. She filed a whistleblower complaint in September, then sued NIH and HHS in December, alleging that her firing was illegal and asking to be reinstated with back pay.

“Putting up resistance to the sort of RFK-speak that was infiltrating the leadership discussions at that time certainly didn’t help my case,” said Marrazzo, who is the CEO of the nonprofit Infectious Diseases Society of America.

Of the NIH institute directors no longer in their roles, six retired after Trump took office. Four were placed on administrative leave then fired midterm. Another was placed on administrative leave then resigned. Two left after NIH did not renew their contracts.

Current and former staffers view some of the oustings as ideologically driven.

Kennedy has pledged that NIH will investigate subjects of personal interest to him, such as purported vaccine injuries and the root causes of autism. (Before going into politics, Kennedy was an anti-vaccine activist.) And Trump issued an executive order in August requiring federal grants to be “consistent with agency priorities and the national interest.” Some of the administration’s attempts to cancel research grants that focused on topics like gender, diversity, equity and inclusion have been reversed, but roughly 1,240 grants remain terminated, according to a tracking project called Grant Witness.

“These leaders who have been removed, many of them were speaking up and pushing back. So when they were removed, I think that very much was received, and was likely intended, as a warning,” said Jenna Norton, a program director at the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases who was placed on administrative leave in November.

Norton filed a whistleblower complaint last week alleging that she was put on leave for speaking out against the politicization of scientific research.

Nixon, however, said concerns that ideology is driving decisions about institute directors are “unfounded.”

A series of oustings

To hire directors for NIH institutes, a search committee typically finds and interviews candidates, then recommends finalists to the agency’s director (Bhattacharya in this case), who chooses which person to nominate.

But at a Senate committee hearing last week about changes at NIH, Bhattacharya — a former Stanford Medicine professor known for his opposition to lockdowns during the height of the Covid pandemic — said that’s no longer the method.

“We’ve changed the process so that there’s no formal committee because we don’t have time for that,” he said. “What we’ve done instead is we’ve informally reached out to external partners, but we’ve also made sure that scientists at the NIH are the ones that are leading the selection of the new leaders.”

One of the most controversial leadership shake-ups at NIH took place in the fall at the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences, which conducts and funds research on how the environment affects human health.

Richard Woychik, who had directed the institute for five years, was appointed to a second term in June. But in October, NIH announced that Woychik had been moved to a different role, and Kyle Walsh, a brain cancer epidemiologist and close friend of Vice President JD Vance’s (Walsh officiated Vance’s wedding), was taking over.

Some employees questioned why Walsh had been chosen, given that his research focus was quite different from that of the institute.

Nixon said in a statement that Walsh “was selected because his scientific background and leadership experience directly align with the NIEHS mission.”

Many NIH staffers also puzzled over the removal of Dr. Walter Koroshetz, who directed the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS) until his contract was not renewed in December. In an email to staff viewed by NBC News, Bhattacharya wrote: “Dr. Koroshetz’s performance has been exceptional; however, the Department of Health and Human Services elected to pursue a leadership transition.”

“It’s an interesting way of saying the NIH director did not seem to have any input into that decision,” Prasad said.

In a letter to Congress last month, 40 organizations representing neuroscience researchers, clinicians and patients expressed concern about the lack of a clear plan for appointing a new director of NINDS, which funds Alzheimer’s research.

“Continuity of leadership is key in ensuring that NINDS is able to discover the next generation of treatments and cures for neurological conditions,” the groups wrote.

Not all of the new directors at NIH have been controversial, however. Zerhouni said the selection of Dr. Anthony Letai, a renowned oncologist and researcher, to run the National Cancer Institute did not seem ideologically driven. (Unlike other director roles, the NCI director is appointed by the president.)

As for the future of NIH, Zerhouni said, avoiding chaos is essential for attracting talent and maintaining the competitiveness of U.S. biomedical research.

“I always saw NIH as a component of our national security and our national competitiveness,” he said. “It’s not going to be the same strength that we expressed in the past 75 years if we continue to do what we’re seeing, or there’s a reduction in the human capital that we need to be competitive.”